Sorrows of Tea

The Sorrows of the Tea

The Sorrows of the Tea

Upon arrival at the town, I was greeted by its name. The air, though transparent with the yellow mist of the sun, blossomed with a soothing smell of green tea. Though the sun hasn’t completely risen beyond the crest of the valley, it spilled a spoon of light over the rooftops as if they are the scales of the golden dragon. Yet, I was interrupted by the flashy red pictures on the walls.

Mr. Weng and his son came out and greeted me. Mr. Weng was a decent looking man, he has a rigid body and a tanned skin. When he smile, his face would fold together like the ridges of the mountains. He shook my hands and welcomed me to the motherland of the tea.

Their home was modest: a smooth concrete floor, a television, three old bamboo chairs, and on the walls hung a big portrait of a man with several servants behind him. The man in the center was wearing a fresh suit. The servants or the farmers behind him (I couldn’t tell if they are authentic farmers, they have a face that is cleaner than mine) smiled happily and held their hands high, clapping. On the bottom it stated, “When drinking water, remember the well digger; when getting rich, remember the Party’s kindness!” As I settled and put down my luggage, I heard a fragment conversation from the phone call of Mr. Weng, “I’m sorry, I only have 30 pounds this year. The week of heat messed up the entire tea cycle.”

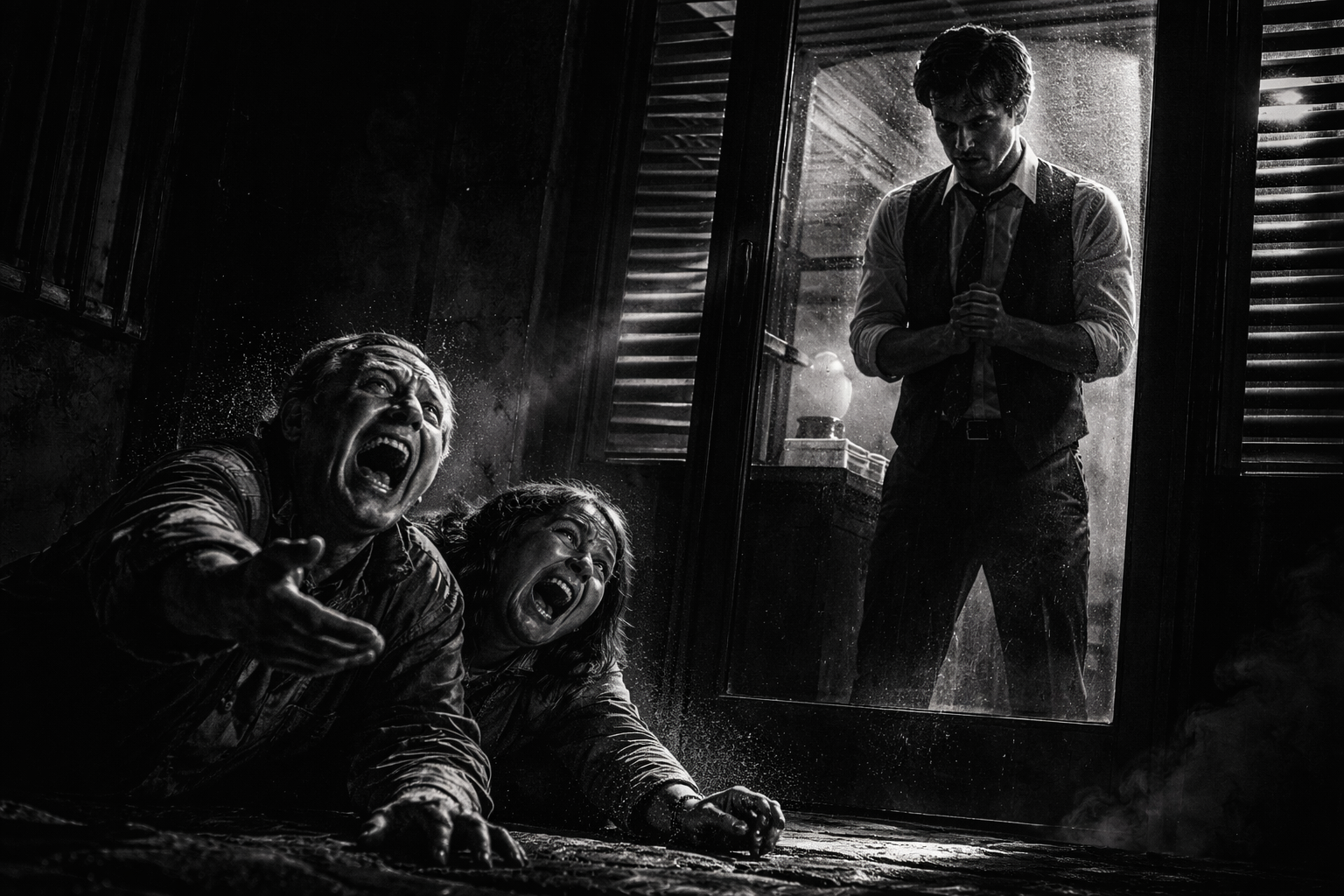

Afternoon, I joined Mr. Weng’ son in the tea harvesting. The shrieking wind stung at my fingers as I moved around each tea plant. The golden dragon above was beaming with his force, the plain reflection of the duplet could have sent me into numbness. My body curved, my knees touched the ground, I held my hand weakly in front of me. “Mercy, Oh forgive me. Mercy!” The dragon rose higher. My sweat mingled with dew on the tip of my nose. One drop, two drops, three drops. I prayed as I watch the old ladies around me kept on picking the fresh new tips of the tea. I looked at myself, my basket a pitiful fraction of theirs. I asked the Mr. Weng’s son: “Who are they?” He responded, “If you recall the poster you saw while entering the village, of the young women with the straw hats collecting the fresh tea leaves, well, it’s them 40 years ago. However, they are the only generation you will ever see.”

“Why?” I asked.

“This is the tragedy of the century. Working so hard but still hungry. For the girls who decide to be a tea harvester, they are forever limited by the work they do. More, and more worthless each year,” sighed Mr. Weng’s son.

“This is nonsense. How could you be not free in a free society? How could…”

That night, I was sitting next to Mr. Weng at a small fire pit. I looked at him as he stirred the pit. The wood and charcoal popped as he stirred the wood each time. I could see the reflection of the sparkles in his eyes. He looked at the portrait above and murmured, “They call us the nation’s backbone, but I can’t get paid enough to mend a broken one. I remember last year’s storm took half our crop. But the posters say we got 50 percent more…”